astro.wikisort.org - Researcher

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ (French: [pjɛʁ tɛjaʁ də ʃaʁdɛ̃] (![]() listen (help·info)); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philosophical books.

listen (help·info)); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philosophical books.

The Reverend Dr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 May 1881 Orcines, Puy-de-Dôme, France |

| Died | 10 April 1955 (aged 73) New York City, US |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Notable work |

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

Main interests |

|

Notable ideas |

|

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

He took part in the discovery of Peking Man. He conceived the vitalist idea of the Omega Point. With Vladimir Vernadsky he developed the concept of the noosphere.

In 1962, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith condemned several of Teilhard's works based on their alleged ambiguities and doctrinal errors. Some eminent Catholic figures, including Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis, have made positive comments on some of his ideas since. The response to his writings by scientists has been mostly critical.

Teilhard served in World War I as a stretcher-bearer. He received several citations, and was awarded the Médaille militaire and the Legion of Honor, the highest French order of merit, both military and civil.

Life

Early years

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born in the Château of Sarcenat, Orcines, some four km (2.5 mi) north-west of Clermont-Ferrand, Auvergne, French Third Republic, on 1 May 1881, as the fourth of eleven children of librarian Emmanuel Teilhard de Chardin (1844–1932) and Berthe-Adèle, née de Dompierre d'Hornoys of Picardy, a great-grandniece of Voltaire. He inherited the double surname from his father, who was descended on the Teilhard side from an ancient family of magistrates from Auvergne originating in Murat, Cantal, ennobled under Louis XVIII of France.[2][3]

His father, a graduate of the École Nationale des Chartes, served as a regional librarian and was a keen naturalist. He collected rocks, insects and plants and encouraged nature studies in the family. Pierre Teilhard's spirituality was awakened by his mother. When he was twelve, he went to the Jesuit college of Mongré in Villefranche-sur-Saône, where he completed the Baccalauréat in philosophy and mathematics. In 1899, he entered the Jesuit novitiate in Aix-en-Provence.[4] In October 1900, he began his junior studies at the Collégiale Saint-Michel de Laval. On 25 March 1901, he made his first vows. In 1902, Teilhard completed a licentiate in literature at the University of Caen.

That same year the Émile Combes premiership took over from Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau in pursuit of an anti-clerical agenda. As a result, religious associations had to submit their properties to state control, which obliged the Jesuits to go into exile in the United Kingdom. Theilhard continued his philosophical studies on the island of Jersey until 1905. Strong in science subjects, he was despatched to teach physics at the Collège de la Sainte Famille in Cairo, Khedivate of Egypt until 1908. From there he wrote in a letter: "[I]t is the dazzling of the East foreseen and drunk greedily ... in its lights, its vegetation, its fauna and its deserts."[5]

For the next four years he was a Scholastic at Ore Place in Hastings, East Sussex where he acquired his theological formation.[4] There he synthesized his scientific, philosophical and theological knowledge in the light of evolution. At that time he read Creative Evolution by Henri Bergson, about which he wrote that "the only effect that brilliant book had upon me was to provide fuel at just the right moment, and very briefly, for a fire that was already consuming my heart and mind."[6] Bergson's ideas were influential on his views on matter, life, and energy. On 24 August 1911, aged 30, he was ordained priest.[4]

Academic career

Paleontology

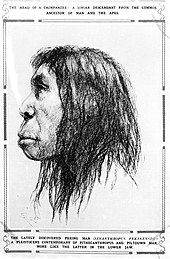

From 1912 to 1914, Teilhard worked in the paleontology laboratory of the National Museum of Natural History, France, studying the mammals of the middle Tertiary period. Later he studied elsewhere in Europe. In June 1912 he formed part of the original digging team, with Arthur Smith Woodward and Charles Dawson, at the Piltdown site, after the discovery of the first fragments of the fraudulent "Piltdown Man". Some have suggested he participated in the hoax.[7][8] Marcellin Boule, a specialist in Neanderthal studies, who as early as 1915 had recognized the non-hominid origins of the Piltdown finds, gradually guided Teilhard towards human paleontology. At the museum's Institute of Human Paleontology, he became a friend of Henri Breuil and in 1913 took part with him in excavations at the prehistoric painted Cave of El Castillo in northwest Spain.

Service in World War I

Mobilized in December 1914, Teilhard served in World War I as a stretcher-bearer in the 8th Moroccan Rifles. For his valor, he received several citations, including the Médaille militaire and the Legion of Honor.

During the war, he developed his reflections in his diaries and in letters to his cousin, Marguerite Teillard-Chambon, who later published a collection of them. (See section below)[9][10] He later wrote: "...the war was a meeting ... with the Absolute." In 1916, he wrote his first essay: La Vie Cosmique (Cosmic life), where his scientific and philosophical thought was revealed just as his mystical life. While on leave from the military he pronounced his solemn vows as a Jesuit in Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon on 26 May 1918. In August 1919, in Jersey, he wrote Puissance spirituelle de la Matière (The Spiritual Power of Matter).

At the University of Paris, Teilhard pursued three unit degrees of natural science: geology, botany, and zoology. His thesis treated the mammals of the French lower Eocene and their stratigraphy. After 1920, he lectured in geology at the Catholic Institute of Paris and after earning a science doctorate in 1922 became an assistant professor there.

Research in China

In 1923 he traveled to China with Father Émile Licent, who was in charge of a significant laboratory collaboration between the National Museum of Natural History and Marcellin Boule's laboratory in Tianjin. Licent carried out considerable basic work in connection with missionaries who accumulated observations of a scientific nature in their spare time.

Teilhard wrote several essays, including La Messe sur le Monde (the Mass on the World), in the Ordos Desert. In the following year, he continued lecturing at the Catholic Institute and participated in a cycle of conferences for the students of the Engineers' Schools. Two theological essays on original sin were sent to a theologian at his request on a purely personal basis:

- July 1920: Chute, Rédemption et Géocentrie (Fall, Redemption and Geocentry)

- Spring 1922: Notes sur quelques représentations historiques possibles du Péché originel (Note on Some Possible Historical Representations of Original Sin) (Works, Tome X)

The Church required him to give up his lecturing at the Catholic Institute in order to continue his geological research in China.

Teilhard traveled again to China in April 1926. He would remain there for about twenty years, with many voyages throughout the world. He settled until 1932 in Tianjin with Émile Licent, then in Beijing. Teilhard made five geological research expeditions in China between 1926 and 1935. They enabled him to establish a general geological map of China.

That same year, Teilhard's superiors in the Jesuit Order forbade him to teach any longer.

In 1926–27, after a missed campaign in Gansu, Teilhard traveled in the Sanggan River Valley near Kalgan (Zhangjiakou) and made a tour in Eastern Mongolia. He wrote Le Milieu Divin (The Divine Milieu). Teilhard prepared the first pages of his main work Le Phénomène Humain (The Phenomenon of Man). The Holy See refused the Imprimatur for Le Milieu Divin in 1927.

He joined the ongoing excavations of the Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian as an advisor in 1926 and continued in the role for the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the China Geological Survey following its founding in 1928. Teilhard resided in Manchuria with Émile Licent, staying in western Shanxi and northern Shaanxi with the Chinese paleontologist Yang Zhongjian and with Davidson Black, Chairman of the China Geological Survey.

After a tour in Manchuria in the area of Greater Khingan with Chinese geologists, Teilhard joined the team of American Expedition Center-Asia in the Gobi Desert, organized in June and July by the American Museum of Natural History with Roy Chapman Andrews. Henri Breuil and Teilhard discovered that the Peking Man, the nearest relative of Anthropopithecus from Java, was a faber (worker of stones and controller of fire). Teilhard wrote L'Esprit de la Terre (The Spirit of the Earth).

Teilhard took part as a scientist in the Croisière Jaune (Yellow Cruise) financed by André Citroën in Central Asia. Northwest of Beijing in Kalgan, he joined the Chinese group who joined the second part of the team, the Pamir group, in Aksu City. He remained with his colleagues for several months in Ürümqi, capital of Xinjiang.

In 1933, Rome ordered him to give up his post in Paris. Teilhard subsequently undertook several explorations in the south of China. He traveled in the valleys of the Yangtze and Sichuan in 1934, then, the following year, in Guangxi and Guangdong. The relationship with Marcellin Boule was disrupted; the museum cut its financing on the grounds that Teilhard worked more for the Chinese Geological Service than for the museum.[citation needed]

During all these years, Teilhard contributed considerably to the constitution of an international network of research in human paleontology related to the whole of eastern and southeastern Asia. He would be particularly associated in this task with two friends, Davidson Black and the Scot George Brown Barbour. Often he would visit France or the United States, only to leave these countries for further expeditions.

World travels

From 1927 to 1928, Teilhard based himself in Paris. He journeyed to Leuven, Belgium, and to Cantal and Ariège, France. Between several articles in reviews, he met new people such as Paul Valéry and Bruno de Solages, who were to help him in issues with the Catholic Church.

Answering an invitation from Henry de Monfreid, Teilhard undertook a journey of two months in Obock, in Harar in the Ethiopian Empire, and in Somalia with his colleague Pierre Lamarre, a geologist, before embarking in Djibouti to return to Tianjin. While in China, Teilhard developed a deep and personal friendship with Lucile Swan.[11]

During 1930–1931, Teilhard stayed in France and in the United States. During a conference in Paris, Teilhard stated: "For the observers of the Future, the greatest event will be the sudden appearance of a collective humane conscience and a human work to make." From 1932 to 1933, he began to meet people to clarify issues with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith regarding Le Milieu divin and L'Esprit de la Terre. He met Helmut de Terra, a German geologist in the International Geology Congress in Washington, D.C.

Teilhard participated in the 1935 Yale–Cambridge expedition in northern and central India with the geologist Helmut de Terra and Patterson, who verified their assumptions on Indian Paleolithic civilisations in Kashmir and the Salt Range Valley. He then made a short stay in Java, on the invitation of Dutch paleontologist Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald to the site of Java Man. A second cranium, more complete, was discovered. Professor von Koenigswald had also found a tooth in a Chinese apothecary shop in 1934 that he believed belonged to a three-meter-tall ape, Gigantopithecus, which lived between one hundred thousand and around a million years ago. Fossilized teeth and bone (dragon bones) are often ground into powder and used in some branches of traditional Chinese medicine.[12]

In 1937, Teilhard wrote Le Phénomène spirituel (The Phenomenon of the Spirit) on board the boat Empress of Japan, where he met Sylvia Brett, Ranee of Sarawak[13] The ship conveyed him to the United States. He received the Mendel Medal granted by Villanova University during the Congress of Philadelphia, in recognition of his works on human paleontology. He made a speech about evolution, the origins and the destiny of man. The New York Times dated 19 March 1937 presented Teilhard as the Jesuit who held that man descended from monkeys. Some days later, he was to be granted the Doctor Honoris Causa distinction from Boston College. Upon arrival in that city, he was told that the award had been cancelled.[citation needed]

Rome banned his work L’Énergie Humaine in 1939. By this point Teilhard was based again in France, where he was immobilized by malaria. During his return voyage to Beijing he wrote L'Energie spirituelle de la Souffrance (Spiritual Energy of Suffering) (Complete Works, tome VII).

In 1941, Teilhard submitted to Rome his most important work, Le Phénomène Humain. By 1947, Rome forbade him to write or teach on philosophical subjects. The next year, Teilhard was called to Rome by the Superior General of the Jesuits who hoped to acquire permission from the Holy See for the publication of Le Phénomène Humain. However, the prohibition to publish it that was previously issued in 1944 was again renewed. Teilhard was also forbidden to take a teaching post in the Collège de France. Another setback came in 1949, when permission to publish Le Groupe Zoologique was refused.

Teilhard was nominated to the French Academy of Sciences in 1950. He was forbidden by his Superiors to attend the International Congress of Paleontology in 1955. The Supreme Authority of the Holy Office, in a decree dated 15 November 1957, forbade the works of de Chardin to be retained in libraries, including those of religious institutes. His books were not to be sold in Catholic bookshops and were not to be translated into other languages.

Further resistance to Teilhard's work arose elsewhere. In April 1958, all Jesuit publications in Spain ("Razón y Fe", "Sal Terrae","Estudios de Deusto", etc.) carried a notice from the Spanish Provincial of the Jesuits that Teilhard's works had been published in Spanish without previous ecclesiastical examination and in defiance of the decrees of the Holy See. A decree of the Holy Office dated 30 June 1962, under the authority of Pope John XXIII, warned:

[I]t is obvious that in philosophical and theological matters, the said works [Teilhard's] are replete with ambiguities or rather with serious errors which offend Catholic doctrine. That is why... the Rev. Fathers of the Holy Office urge all Ordinaries, Superiors, and Rectors... to effectively protect, especially the minds of the young, against the dangers of the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and his followers.[14]

The Diocese of Rome on 30 September 1963 required Catholic booksellers in Rome to withdraw his works as well as those that supported his views.[15]

Death

Teilhard died in New York City, where he was in residence at the Jesuit Church of St. Ignatius Loyola, Park Avenue. On 15 March 1955, at the house of his diplomat cousin Jean de Lagarde, Teilhard told friends he hoped he would die on Easter Sunday.[16] On the evening of Easter Sunday, 10 April 1955, during an animated discussion at the apartment of Rhoda de Terra, his personal assistant since 1949, Teilhard suffered a heart attack and died.[16] He was buried in the cemetery for the New York Province of the Jesuits at the Jesuit novitiate, St. Andrew-on-Hudson, in Hyde Park, New York. With the moving of the novitiate, the property was sold to the Culinary Institute of America in 1970.

Teachings

Teilhard de Chardin wrote two comprehensive works, The Phenomenon of Man and The Divine Milieu.[17]

His posthumously published book, The Phenomenon of Man, set forth a sweeping account of the unfolding of the cosmos and the evolution of matter to humanity, to ultimately a reunion with Christ. In the book, Teilhard abandoned literal interpretations of creation in the Book of Genesis in favor of allegorical and theological interpretations. The unfolding of the material cosmos is described from primordial particles to the development of life, human beings and the noosphere, and finally to his vision of the Omega Point in the future, which is "pulling" all creation towards it. He was a leading proponent of orthogenesis, the idea that evolution occurs in a directional, goal-driven way. Teilhard argued in Darwinian terms with respect to biology, and supported the synthetic model of evolution, but argued in Lamarckian terms for the development of culture, primarily through the vehicle of education.[18]

Teilhard made a total commitment to the evolutionary process in the 1920s as the core of his spirituality, at a time when other religious thinkers felt evolutionary thinking challenged the structure of conventional Christian faith. He committed himself to what the evidence showed.[19]

Teilhard made sense of the universe by assuming it had a vitalist evolutionary process.[20][21] He interprets complexity as the axis of evolution of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, into consciousness (in man), and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point). Jean Houston's story of meeting Teilhard illustrates this point.[22]

Teilhard's unique relationship to both paleontology and Catholicism allowed him to develop a highly progressive, cosmic theology which took into account his evolutionary studies. Teilhard recognized the importance of bringing the Church into the modern world, and approached evolution as a way of providing ontological meaning for Christianity, particularly creation theology. For Teilhard, evolution was "the natural landscape where the history of salvation is situated."[23]

Teilhard's cosmic theology is largely predicated on his interpretation of Pauline scripture, particularly Colossians 1:15-17 (especially verse 1:17b) and 1 Corinthians 15:28. He drew on the Christocentrism of these two Pauline passages to construct a cosmic theology which recognizes the absolute primacy of Christ. He understood creation to be "a teleological process towards union with the Godhead, effected through the incarnation and redemption of Christ, 'in whom all things hold together' (Col. 1:17)."[24] He further posited that creation would not be complete until each "participated being is totally united with God through Christ in the Pleroma, when God will be 'all in all' (1Cor. 15:28)."[24]

Teilhard's life work was predicated on his conviction that human spiritual development is moved by the same universal laws as material development. He wrote, "...everything is the sum of the past" and "...nothing is comprehensible except through its history. 'Nature' is the equivalent of 'becoming', self-creation: this is the view to which experience irresistibly leads us. ... There is nothing, not even the human soul, the highest spiritual manifestation we know of, that does not come within this universal law."[25]

The Phenomenon of Man represents Teilhard's attempt at reconciling his religious faith with his academic interests as a paleontologist.[26] One particularly poignant observation in Teilhard's book entails the notion that evolution is becoming an increasingly optional process.[26] Teilhard points to the societal problems of isolation and marginalization as huge inhibitors of evolution, especially since evolution requires a unification of consciousness. He states that "no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else."[26] Teilhard argued that the human condition necessarily leads to the psychic unity of humankind, though he stressed that this unity can only be voluntary; this voluntary psychic unity he termed "unanimization". Teilhard also states that "evolution is an ascent toward consciousness", giving encephalization as an example of early stages, and therefore, signifies a continuous upsurge toward the Omega Point[26] which, for all intents and purposes, is God.

Teilhard also used his perceived correlation between spiritual and material to describe Christ, arguing that Christ not only has a mystical dimension but also takes on a physical dimension as he becomes the organizing principle of the universe—that is, the one who "holds together" the universe (Col. 1:17b). For Teilhard, Christ forms not only the eschatological end toward which his mystical/ecclesial body is oriented, but he also "operates physically in order to regulate all things"[27] becoming "the one from whom all creation receives its stability."[28] In other words, as the one who holds all things together, "Christ exercises a supremacy over the universe which is physical, not simply juridical. He is the unifying center of the universe and its goal. The function of holding all things together indicates that Christ is not only man and God; he also possesses a third aspect—indeed, a third nature—which is cosmic."[29]

In this way, the Pauline description of the Body of Christ is not simply a mystical or ecclesial concept for Teilhard; it is cosmic. This cosmic Body of Christ "extend[s] throughout the universe and compris[es] all things that attain their fulfillment in Christ [so that] ... the Body of Christ is the one single thing that is being made in creation."[30] Teilhard describes this cosmic amassing of Christ as "Christogenesis". According to Teilhard, the universe is engaged in Christogenesis as it evolves toward its full realization at Omega, a point which coincides with the fully realized Christ.[24] It is at this point that God will be "all in all" (1Cor. 15:28c).

Our century is probably more religious than any other. How could it fail to be, with such problems to be solved? The only trouble is that it has not yet found a God it can adore.[26]

Tielhard has been criticized as incorporating common notions of Social Darwinism and scientific racism into his work, along with support for eugenics, though he has also been defended by theologian John Haught.[31][32][33]

Relationship with the Catholic Church

In 1925, Teilhard was ordered by the Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, to leave his teaching position in France and to sign a statement withdrawing his controversial statements regarding the doctrine of original sin. Rather than leave the Society of Jesus, Teilhard signed the statement and left for China.[citation needed]

This was the first of a series of condemnations by a range of ecclesiastical officials that would continue until after Teilhard's death. The climax of these condemnations was a 1962 monitum (warning) of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith cautioning on Teilhard's works. It said:[34]

Several works of Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, some of which were posthumously published, are being edited and are gaining a good deal of success. Prescinding from a judgement about those points that concern the positive sciences, it is sufficiently clear that the above-mentioned works abound in such ambiguities and indeed even serious errors, as to offend Catholic doctrine. For this reason, the most eminent and most revered Fathers of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries as well as the superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers.

The Holy Office did not, however, place any of Teilhard's writings on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books), which still existed during Teilhard's lifetime and at the time of the 1962 decree.

Shortly thereafter, prominent clerics mounted a strong theological defense of Teilhard's works. Henri de Lubac (later a Cardinal) wrote three comprehensive books on the theology of Teilhard de Chardin in the 1960s.[35] While de Lubac mentioned that Teilhard was less than precise in some of his concepts, he affirmed the orthodoxy of Teilhard de Chardin and responded to Teilhard's critics: "We need not concern ourselves with a number of detractors of Teilhard, in whom emotion has blunted intelligence".[36] Later that decade Joseph Ratzinger, a German theologian who became Pope Benedict XVI, spoke glowingly of Teilhard's Christology in Ratzinger's Introduction to Christianity:[37]

It must be regarded as an important service of Teilhard de Chardin's that he rethought these ideas from the angle of the modern view of the world and, in spite of a not entirely unobjectionable tendency toward the biological approach, nevertheless on the whole grasped them correctly and in any case made them accessible once again.

Over the next several decades prominent theologians and prelates, including leading cardinals all wrote approvingly of Teilhard's ideas. In 1981, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, wrote on the front page of the Vatican newspaper, l'Osservatore Romano:

What our contemporaries will undoubtedly remember, beyond the difficulties of conception and deficiencies of expression in this audacious attempt to reach a synthesis, is the testimony of the coherent life of a man possessed by Christ in the depths of his soul. He was concerned with honoring both faith and reason, and anticipated the response to John Paul II's appeal: "Be not afraid, open, open wide to Christ the doors of the immense domains of culture, civilization, and progress".[38]

On 20 July 1981, the Holy See stated that, after consultation of Cardinal Casaroli and Cardinal Franjo Šeper, the letter did not change the position of the warning issued by the Holy Office on 30 June 1962, which pointed out that Teilhard's work contained ambiguities and grave doctrinal errors.[39]

Cardinal Ratzinger in his book The Spirit of the Liturgy incorporates Teilhard's vision as a touchstone of the Catholic Mass:[40]

And so we can now say that the goal of worship and the goal of creation as a whole are one and the same—divinization, a world of freedom and love. But this means that the historical makes its appearance in the cosmic. The cosmos is not a kind of closed building, a stationary container in which history may by chance take place. It is itself movement, from its one beginning to its one end. In a sense, creation is history. Against the background of the modern evolutionary world view, Teilhard de Chardin depicted the cosmos as a process of ascent, a series of unions. From very simple beginnings the path leads to ever greater and more complex unities, in which multiplicity is not abolished but merged into a growing synthesis, leading to the "Noosphere" in which spirit and its understanding embrace the whole and are blended into a kind of living organism. Invoking the epistles to the Ephesians and Colossians, Teilhard looks on Christ as the energy that strives toward the Noosphere and finally incorporates everything in its "fullness". From here Teilhard went on to give a new meaning to Christian worship: the transubstantiated Host is the anticipation of the transformation and divinization of matter in the christological "fullness". In his view, the Eucharist provides the movement of the cosmos with its direction; it anticipates its goal and at the same time urges it on.

Cardinal Avery Dulles said in 2004:[41]

In his own poetic style, the French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin liked to meditate on the Eucharist as the first fruits of the new creation. In an essay called The Monstrance he describes how, kneeling in prayer, he had a sensation that the Host was beginning to grow until at last, through its mysterious expansion, "the whole world had become incandescent, had itself become like a single giant Host". Although it would probably be incorrect to imagine that the universe will eventually be transubstantiated, Teilhard correctly identified the connection between the Eucharist and the final glorification of the cosmos.

Cardinal Christoph Schönborn wrote in 2007:[42]

Hardly anyone else has tried to bring together the knowledge of Christ and the idea of evolution as the scientist (paleontologist) and theologian Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., has done. ... His fascinating vision ... has represented a great hope, the hope that faith in Christ and a scientific approach to the world can be brought together. ... These brief references to Teilhard cannot do justice to his efforts. The fascination which Teilhard de Chardin exercised for an entire generation stemmed from his radical manner of looking at science and Christian faith together.

In July 2009, Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi said, "By now, no one would dream of saying that [Teilhard] is a heterodox author who shouldn't be studied."[43]

Fr Donal Dorr (Theologian) refers to Teilhard in his 2020 book: A Creed for Today. Faith and Commitment for our New Earth Awareness.

Pope Francis refers to Teilhard's eschatological contribution in his encyclical Laudato si'.[44]

The philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand criticized severely the work of Teilhard. According to Hildebrand, in a conversation after a lecture by Teilhard: "He (Teilhard) ignored completely the decisive difference between nature and supernature. After a lively discussion in which I ventured a criticism of his ideas, I had an opportunity to speak to Teilhard privately. When our talk touched on St. Augustine, he exclaimed violently: 'Don’t mention that unfortunate man; he spoiled everything by introducing the supernatural.'"[45] Von Hildebrand writes that Teilhardism is incompatible with Christianity, substitutes efficiency for sanctity, dehumanizes man, and describes love as merely cosmic energy.

Evaluations by scientists

Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley, the evolutionary biologist, in the preface to the 1955 edition of The Phenomenon of Man, praised the thought of Teilhard de Chardin for looking at the way in which human development needs to be examined within a larger integrated universal sense of evolution, though admitting he could not follow Teilhard all the way.[46]

Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Dobzhansky, writing in 1973, drew upon Teilhard's insistence that evolutionary theory provides the core of how man understands his relationship to nature, calling him "one of the great thinkers of our age".[47]

Daniel Dennett

According to Daniel Dennett (1995), "it has become clear to the point of unanimity among scientists that Teilhard offered nothing serious in the way of an alternative to orthodoxy; the ideas that were peculiarly his were confused, and the rest was just bombastic redescription of orthodoxy."[48]

Steven Rose

Steven Rose wrote[year needed] that "Teilhard is revered as a mystic of genius by some, but among most biologists is seen as little more than a charlatan."[49]

Peter Medawar

In 1961, British immunologist and Nobel laureate Peter Medawar wrote a scornful review of The Phenomenon of Man for the journal Mind: "the greater part of it [...] is nonsense, tricked out with a variety of metaphysical conceits, and its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself. [...] Teilhard practiced an intellectually unexacting kind of science [...]. He has no grasp of what makes a logical argument or what makes for proof. He does not even preserve the common decencies of scientific writing, though his book is professedly a scientific treatise. [...] Teilhard habitually and systematically cheats with words [...], uses in metaphor words like energy, tension, force, impetus, and dimension as if they retained the weight and thrust of their special scientific usages. [...] It is the style that creates the illusion of content."[50]

Richard Dawkins

Evolutionary biologist and New Atheist Richard Dawkins called Medawar's review "devastating" and The Phenomenon of Man "the quintessence of bad poetic science".[51]

George Gaylord Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson felt that if Teilhard were right, the lifework "of Huxley, Dobzhansky, and hundreds of others was not only wrong, but meaningless", and was mystified by their public support for him.[52] He considered Teilhard a friend and his work in paleontology extensive and important, but expressed strongly adverse views of his contributions as scientific theorist and philosopher.[53]

David Sloan Wilson

In 2019, evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson praised Teilhard's book The Phenomenon of Man as "scientifically prophetic in many ways", and considers his own work as an updated version of it, commenting that[54] "[m]odern evolutionary theory shows that what Teilhard meant by the Omega Point is achievable in the foreseeable future."

Wolfgang Smith

Wolfgang Smith, an American scientist versed in Catholic theology, devotes an entire book to the critique of Teilhard's doctrine, which he considers neither scientific (assertions without proofs), nor Catholic (personal innovations), nor metaphysical (the "Absolute Being" is not yet absolute),[55] and of which the following elements can be noted (all the words in quotation marks are Teilhard's, quoted by Smith) :

Evolution

Smith claims that for Teilhard, evolution is not only a scientific theory but an irrefutable truth "immune from any subsequent contradiction by experience ";[56] it constitutes the foundation of his doctrine.[57] Matter becomes spirit and humanity moves towards a super-humanity thanks to complexification (physico-chemical, then biological, then human), socialization, scientific research and technological and cerebral development;[58] the explosion of the first atomic bomb is one of its milestones,[59] while waiting for "the vitalization of matter by the creation of super-molecules, the remodeling of the human organism by means of hormones, control of heredity and sex by manipulation of genes and chromosomes [...]".[60]

Matter and spirit

Teilhard maintains that the human spirit (which he identifies with the anima and not with the spiritus) originates in a matter which becomes more and more complex until it produces life, then consciousness, then the consciousness of being conscious, holding that the immaterial can emerge from the material.[61] At the same time, he supports the idea of the presence of embryos of consciousness from the very genesis of the universe: "We are logically forced to assume the existence [...] of some sort of psyche" infinitely diffuse in the smallest particle.[62]

Theology

Smith believes that since Teilhard affirms that "God creates evolutively", he denies the Book of Genesis,[63] not only because it attests that God created man, but that he created him in his own image, thus perfect and complete, then that man fell, that is to say the opposite of an ascending evolution.[64] That which is metaphysically and theologically "above" - symbolically speaking - becomes for Teilhard "ahead", yet to come;[65] even God, who is neither perfect nor timeless, evolves in symbiosis with the World,[note 1] which Teilhard, a resolute pantheist,[66] venerates as the equal of the Divine.[67] As for Christ, not only is he there to activate the wheels of progress and complete the evolutionary ascent, but he himself evolves.[note 2].[68]

New religion

As he wrote to a cousin: "What dominates my interests increasingly is the effort to establish in me and define around me a new religion (call it a better Christianity, if you will)...",[69] and elsewhere: "a Christianity re-incarnated for a second time in the spiritual energies of Matter".[70] The more Teilhard refines his theories, the more he emancipates himself from established Christian doctrine:[71] a "religion of the earth" must replace a "religion of heaven".[72] By their common faith in Man, he writes, Christians, Marxists, Darwinists, materialists of all kinds will ultimately join around the same summit: the Christic Omega Point.[73]

Legacy

Brian Swimme wrote "Teilhard was one of the first scientists to realize that the human and the universe are inseparable. The only universe we know about is a universe that brought forth the human."[74]

George Gaylord Simpson named the most primitive and ancient genus of true primate, the Eocene genus Teilhardina.

Influence on arts and culture

Teilhard and his work continue to influence the arts and culture. Characters based on Teilhard appear in several novels, including Jean Telemond in Morris West's The Shoes of the Fisherman[75] (mentioned by name and quoted by Oskar Werner playing Fr. Telemond in the movie version of the novel). In Dan Simmons' 1989–97 Hyperion Cantos, Teilhard de Chardin has been canonized a saint in the far future. His work inspires the anthropologist priest character, Paul Duré. When Duré becomes Pope, he takes Teilhard I as his regnal name.[76] Teilhard appears as a minor character in the play Fake by Eric Simonson, staged by Chicago's Steppenwolf Theatre Company in 2009, involving a fictional solution to the infamous Piltdown Man hoax.

References range from occasional quotations—an auto mechanic quotes Teilhard in Philip K. Dick's A Scanner Darkly[77]—to serving as the philosophical underpinning of the plot, as Teilhard's work does in Julian May's 1987–94 Galactic Milieu Series.[78] Teilhard also plays a major role in Annie Dillard's 1999 For the Time Being.[79] Teilhard is mentioned by name and the Omega Point briefly explained in Arthur C. Clarke's and Stephen Baxter's The Light of Other Days.[80] The title of the short-story collection Everything That Rises Must Converge by Flannery O'Connor is a reference to Teilhard's work. The American novelist Don DeLillo's 2010 novel Point Omega borrows its title and some of its ideas from Teilhard de Chardin.[81] Robert Wright, in his book Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny, compares his own naturalistic thesis that biological and cultural evolution are directional and, possibly, purposeful, with Teilhard's ideas.

Teilhard's work also inspired philosophical ruminations by Italian laureate architect Paolo Soleri and Mexican writer Margarita Casasús Altamirano, artworks such as French painter Alfred Manessier's L'Offrande de la terre ou Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin and American sculptor Frederick Hart's acrylic sculpture The Divine Milieu: Homage to Teilhard de Chardin.[82] A sculpture of the Omega Point by Henry Setter, with a quote from Teilhard de Chardin, can be found at the entrance to the Roesch Library at the University of Dayton.[83] The Spanish painter Salvador Dalí was fascinated by Teilhard de Chardin and the Omega Point theory. His 1959 painting The Ecumenical Council is said to represent the "interconnectedness" of the Omega Point.[84]

Edmund Rubbra's 1968 Symphony No. 8 is titled Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin.

The Embracing Universe, an oratorio for choir and 7 instruments, composed by Justin Grounds to a libretto by Fred LaHaye saw its first performance in 2019. It is based on the life and thought of Teilhard de Chardin.[85]

Several college campuses honor Teilhard. A building at the University of Manchester is named after him, as are residence dormitories at Gonzaga University and Seattle University.

The De Chardin Project, a play celebrating Teilhard's life, ran from 20 November to 14 December 2014 in Toronto, Canada.[86] The Evolution of Teilhard de Chardin, a documentary film on Teilhard's life, was scheduled for release in 2015.[86]

Founded in 1978, George Addair based much of Omega Vector on Teilhard's work.

The American physicist Frank J. Tipler has further developed Teilhard's Omega Point concept in two controversial books, The Physics of Immortality and the more theologically based Physics of Christianity.[87] While keeping the central premise of Teilhard's Omega Point (i.e. a universe evolving towards a maximum state of complexity and consciousness) Tipler has supplanted some of the more mystical/ theological elements of the OPT with his own scientific and mathematical observations (as well as some elements borrowed from Freeman Dyson's eternal intelligence theory).[88][89]

In 1972, the Uruguayan priest Juan Luis Segundo, in his five-volume series A Theology for Artisans of a New Humanity, wrote that Teilhard "noticed the profound analogies existing between the conceptual elements used by the natural sciences — all of them being based on the hypothesis of a general evolution of the universe."[90]

French anthropologist Jean Baudrillard's 1976 book Symbolic Exchange and Death explicitly mentions Teilhard de Chardin.[91] He also mentions the OMega point.[92]

Influence of his cousin, Marguerite

Marguerite Teillard-Chambon, (alias Claude Aragonnès) was a French writer who edited and had published three volumes of correspondence with her cousin, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, "La genèse d'une pensée" ("The Making of a Mind") being the last, after her own death in 1959.[10] She furnished each with an introduction. Marguerite, a year older than Teilhard, was considered among those who knew and understood him best. They had shared a childhood in Auvergne; she it was who encouraged him to undertake a doctorate in science at the Sorbonne; she eased his entry into the Catholic Institute, through her connection to Emmanuel de Margerie and she introduced him to the intellectual life of Paris. Throughout the First World War, she corresponded with him, acting as a "midwife" to his thinking, helping his thought to emerge and honing it. In September 1959 she participated in a gathering organised at Saint-Babel, near Issoire, devoted to Teilhard's philosophical contribution. On the way home to Chambon-sur-Lac, she was fatally injured in a road traffic accident. Her sister, Alice, completed the final preparations for the publication of the final volume of her cousin Teilhard's wartime letters.[93][94][95]

Influence on the New Age movement

Teilhard has had a profound influence on the New Age movements and has been described as "perhaps the man most responsible for the spiritualization of evolution in a global and cosmic context".[96]

Other

Teilhard's words about likening the discovery of the power of love to the second time man will have discovered the power of fire, were quoted in the sermon of the Most Reverend Michael Curry, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, during the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle on 20 May 2018.[97]

Bibliography

The dates in parentheses are the dates of first publication in French and English. Most of these works were written years earlier, but Teilhard's ecclesiastical order forbade him to publish them because of their controversial nature. The essay collections are organized by subject rather than date, thus each one typically spans many years.

- Le Phénomène Humain (1955), written 1938–40, scientific exposition of Teilhard's theory of evolution.

- The Phenomenon of Man (1959), Harper Perennial 1976: ISBN 978-0-06-090495-1. Reprint 2008: ISBN 978-0-06-163265-5.

- The Human Phenomenon (1999), Brighton: Sussex Academic, 2003: ISBN 978-1-902210-30-8.

- Letters From a Traveler (1956; English translation 1962), written 1923–55.

- Le Groupe Zoologique Humain (1956), written 1949, more detailed presentation of Teilhard's theories.

- Man's Place in Nature (English translation 1966).

- Le Milieu Divin (1957), spiritual book written 1926–27, in which the author seeks to offer a way for everyday life, i.e. the secular, to be divinized.

- The Divine Milieu (1960) Harper Perennial 2001: ISBN 978-0-06-093725-6.

- L'Avenir de l'Homme (1959) essays written 1920–52, on the evolution of consciousness (noosphere).

- The Future of Man (1964) Image 2004: ISBN 978-0-385-51072-1.

- Hymn of the Universe (1961; English translation 1965) Harper and Row: ISBN 978-0-06-131910-5, mystical/spiritual essays and thoughts written 1916–55.

- L'Energie Humaine (1962), essays written 1931–39, on morality and love.

- Human Energy (1969) Harcort Brace Jovanovich ISBN 978-0-15-642300-7.

- L'Activation de l'Energie (1963), sequel to Human Energy, essays written 1939–55 but not planned for publication, about the universality and irreversibility of human action.

- Activation of Energy (1970), Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 978-0-15-602817-2.

- Je M'Explique (1966) Jean-Pierre Demoulin, editor ISBN 978-0-685-36593-9, "The Essential Teilhard" — selected passages from his works.

- Let Me Explain (1970) Harper and Row ISBN 978-0-06-061800-1, Collins/Fontana 1973: ISBN 978-0-00-623379-4.

- Christianity and Evolution, Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 978-0-15-602818-9.

- The Heart of the Matter, Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 978-0-15-602758-8.

- Toward the Future, Harvest/HBJ 2002: ISBN 978-0-15-602819-6.

- The Making of a Mind: Letters from a Soldier-Priest 1914–1919, Collins (1965), Letters written during wartime.

- Writings in Time of War, Collins (1968) composed of spiritual essays written during wartime. One of the few books of Teilhard to receive an imprimatur.

- Vision of the Past, Collins (1966) composed of mostly scientific essays published in the French science journal Etudes.

- The Appearance of Man, Collins (1965) composed of mostly scientific writings published in the French science journal Etudes.

- Letters to Two Friends 1926–1952, Fontana (1968). Composed of personal letters on varied subjects including his understanding of death. See Letters to Two Friends 1926–1952. Helen Weaver (translation). 1968. ISBN 978-0-85391-143-2. OCLC 30268456.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Letters to Léontine Zanta, Collins (1969).

- Correspondence / Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Maurice Blondel, Herder and Herder (1967) This correspondence also has both the imprimatur and nihil obstat.

- de Chardin, P T (1952). "On the zoological position and the evolutionary significance of Australopithecines". Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences (published March 1952). 14 (5): 208–10. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1952.tb01101.x. PMID 14931535.

- de Terra, H; de Chardin, PT; Paterson, TT (1936). "Joint geological and prehistoric studies of the Late Cenozoic in India". Science (published 6 March 1936). 83 (2149): 233–236. Bibcode:1936Sci....83..233D. doi:10.1126/science.83.2149.233-a. PMID 17809311.

See also

- Edouard Le Roy

- Thomas Berry

- Henri Bergson

- Henri Breuil

- Henri de Lubac

- Law of Complexity/Consciousness

- List of science and religion scholars

- List of Jesuit scientists

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Noogenesis

Notes

- "I see in the World a mysterious product of completion and fulfillment for the absolute Being himself." The Heart of Matter, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1979, p. 54 - quoted in Wolfgang Smith, Teilhardism and the New Religion, Tan Books & Pub, Gastonia/NC, USA, 1988, p. 104.

- "It is Christ, in all truth, who saves, but should we not immediately add that at the same time it is Christ who is saved by evolution?" The Heart of Matter, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1979, p. 92 - quoted in Wolfgang Smith, Teilhardism and the New Religion, Tan Books & Pub, Gastonia/NC, USA, 1988, p. 117.

References

- Thomas M. King (28 March 2005). "The life of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., the smiling scientist". www.americamagazine.org.

- Paul Marichal, "Emmanuel Teilhard de Chardin (1844-1932)", Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes 93 (1932), 416f. Emmanuel Teilhard de Chardin was the son of Pierre-Cirice Teilhard and of Victoire Teilhard née Barron de Chardin. The grandfather of Pierre-Cirice, Pierre Teilhard, was granted a letter of confirmation of nobility by Louis XVIII in 1816.

- Aczel, Amir (2008). The Jesuit and the Skull. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4406-3735-3.

- Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre (2001). L'expérience de Dieu avec Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (in French). Les Editions Fides. ISBN 978-2-7621-2348-7.

- Letters from Egypt (1905–1908) — Éditions Aubier

- Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre (1979). Hague, René (ed.). The Heart of Matter. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 25.

- "Teilhard and the Pildown "Hoax"". www.clarku.edu. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Wayman, Erin. "How to Solve Human Evolution's Greatest Hoax". Smithsonian. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Genèse d'une pensée (English: "The Making of a Mind")

- de Chardin, Teilhard (1965). The Making of a Mind: Letters from a Soldier-Priest 1914–1919. London: Collins.

- Aczel, Amir (4 November 2008). The Jesuit and the Skull: Teilhard de Chardin, Evolution, and the Search for Peking Man. Riverhead Trade. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-594489-56-3.

- "How Gigantopithecus was discovered". The University of Iowa Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "Letters from a Traveller". Retrieved 26 September 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- AAS, 6 August 1962

- The text of this decree was published in daily L’Aurore of Paris, dated 2 October 1963, and was reproduced in Nouvelles De Chrétienté, 10 October 1963, p. 35.

- Smulders, Pieter Frans (1967). The design of Teilhard de Chardin: an essay in theological reflection. Newman Press.[page needed]

- "The Divine Milieu: Work by Teilhard de Chardin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Teilhard de Chardin, Orthogenesis, and the Mechanism of Evolutionary Change" on YouTube by Thomas F Glick.

- Berry, Thomas (1982) "Teilard de Chardin in the Age of Ecology" (Studies of Teihard de Chardin)

- Normandin, Sebastian; Charles T. Wolfe (15 June 2013). Vitalism and the Scientific Image in Post-Enlightenment Life Science, 1800-2010. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-94-007-2445-7.

vitalism finds occasional expression in the neo-Thomist philosophies associated with Catholicism. Indeed, Catholic philosophy was heavily influenced by bergson in the early twentieth century, and there is a direct link between Bergson's neo-vitalism and the nascent neo-Thomism of thinkers like Jacques Maritain, which led to various idealist interpretations of biology which labeled themselves 'vitalistic', such as those of Edouard Le Roy (influenced by Teilhard de Chardin).

- "(Review of) Howard, Damian.Being Human in Islam: The Impact of the Evolutionary Worldview" (PDF). Teilhard Perspective. 44 (2): 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

the strong influence of Henri Bergson, via the writings of Muhammed Iqbal, who is seen to represent a Romantic, Naturphilosophie school of "vitalist cosmic progressivism," in contrast to Western mechanical materialism. And Teilhard, much akin to the French Bergson, along with Karl Rahner, are rightly noted as latter exemplars of this life-affirmative option.

- "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Galleni, Ludovico; Scalfari, Francesco (2005). "Teilhard de Chardin's Engagement with the Relationship between Science and Theology in Light of Discussions about Environmental Ethics". Ecotheology. 10 (2): 197. doi:10.1558/ecot.2005.10.2.196.

- Lyons, J. A. (1982). The Cosmic Christ in Origen and Teilhard de Chardin: A Comparative Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 39.

- Teilhard de Chardin: "A Note on Progress"

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man (New York: Harper and Row, 1959), 250–75.

- Lyons (1982). The Cosmic Christ in Origen and Teilhard de Chardin. p. 154.

- Lyons (1982). The Cosmic Christ in Origen and Teilhard de Chardin: A Comparative Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 152.

- Lyons (1982). The Cosmic Christ in Origen and Teilhard de Chardin. p. 153.

- Lyons (1982). The Cosmic Christ in Origen and Teilhard de Chardin. pp. 154–155.

- "Pierre Tielhard De Chardin's Legacy of Eugenics and Racism Can't Be Ignored". 21 May 2018.

- "Trashing Teilhard | Commonweal Magazine". www.commonwealmagazine.org. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Teilhard & Eugenics | Commonweal Magazine". www.commonwealmagazine.org. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- O'Connell, Gerard (21 November 2017). "Will Pope Francis remove the Vatican's 'warning' from Teilhard de Chardin's writings?". America. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Wojciech Sadłoń, Teologia Teilharda de Chardin. Studium nad komentarzami Henri de Lubaca, Warszawa, UKSW 2009

- Cardinal Henri Cardinal de Lubac – The Religion of Teilhard de Chardin, Image Books (1968)

- Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal; Pope Benedict XVI; Benedict; J. R. Foster; Michael J. Miller (4 June 2010). Introduction To Christianity, 2nd Edition (Kindle Locations 2840-2865). Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

- "Card. Agostino Casaroli praises the work of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin". www.traditioninaction.org. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Teilhard de Chardin". www.ewtn.com. L'osservatore romano. 20 July 1981. p. 2. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- – Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal; Pope Benedict XVI (11 June 2009). The Spirit of the Liturgy (Kindle Locations 260–270). Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

- A Eucharistic Church: The Vision of John Paul II – McGinley Lecture, University, 10 November 2004

- Cardinal Christoph Schoenborn, Creation, Evolution, and a Rational Faith, Ignatian Press (2007)

- Allen, John (28 July 2009). "Pope cites Teilhardian vision of the cosmos as a 'living host'". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Pope Francis (24 May 2015), ENCYCLICAL LETTER LAUDATO SI' OF THE HOLY FATHER FRANCIS ON CARE FOR OUR COMMON HOME (PDF), Online, p. 61, retrieved 20 June 2015

- Von Hildebrand, Dietrich (1993). Trojan Horse in the City of God. Sophia Inst Pr. ISBN 978-0-918477-18-7.

- Huxley, Julian "Preface" to Teilhard de Chardin, Teilhard (1955) "The Phenomenon of Man" (Fontana)

- Dobzhansky, Theodosius (March 1973). "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution". American Biology Teacher. 35 (3): 125–129. doi:10.2307/4444260. JSTOR 4444260. S2CID 207358177. Reprinted in J. Peter Zetterberg (ed.), Evolution versus Creationism (1983), ORYX Press.

- Dennett, Daniel C. (1995). Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meaning of Life. Simon & Schuster. pp. 320–. ISBN 978-1-4391-2629-5.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2006). The Richness of Life: The Essential Stephen Jay Gould. W.W. Norton. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-393-06498-8.[clarification needed]

- Medawar, P. B. (1961). "Critical Notice". Mind. Oxford University Press. 70 (277): 99–106. doi:10.1093/mind/LXX.277.99.

- Dawkins, Richard (5 April 2000). Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 320ff. ISBN 978-0-547-34735-6.

- Browning, Geraldine O.; Joseph L. Alioto; Seymour M. Farber; University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (January 1973). Teilhard de Chardin: in Quest of the Perfection of Man: An International Symposium. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 91ff. ISBN 978-0-8386-1258-3.

- Laporte, Léo F. (13 August 2013). George Gaylord Simpson: Paleontologist and Evolutionist. Columbia University Press. pp. 191ff. ISBN 978-0-231-50545-1.

- Wilson, David Sloan (26 February 2019). This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-87021-1.

- Wolfgang Smith, Teilhardism and the New Religion: A Thorough Analysis of the Teachings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Tan Books & Pub, Gastonia/NC, USA, 1988 (republished as Theistic Evolution, Angelico Press, New York, 2012, 270 pages).

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, Harper & Row, New York, 1965, p. 140 – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 2.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 2.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., pp. 177, 201.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, Op. cit, p. 149 – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 243-244.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, The Future of Mankind, Harper & Row, New York, 1964, p. 149 – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 243.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., pp. 42-43.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, Op. cit, pp. 301-302 – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., pp. 49-50.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., pp. 13, 19.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 137.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 69.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 110.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 127.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., pp. 117, 127.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, Letters to Léontine Zanta, Harper & Row, New York, 1965, p. 114 (letter of 26 January 1936) – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 210.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, The Heart of Matter, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1979, p. 96 – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 22.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 102.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin, Science and Christ, Collins, London, 1968, p. 120 – quoted in W. Smith, Op. cit., p. 208.

- W. Smith, Op. cit., pp. 22, 188.

- "Introduction" by Brian Swimme, in The Human Phenomenon by Teilhard de Chardin, trans. Sarah Appleton-Webber, Sussex Academic Press, Brighton and Portland, Oregon, 1999 p. xv.

- Moss, R.F. (Spring 1978). "Suffering, sinful Catholics". The Antioch Review. Antioch Review. 36 (2): 170–181. doi:10.2307/4638026. JSTOR 4638026.

- Simmons, Dan (1 February 1990). The Fall of Hyperion. Doubleday. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-385-26747-2.

- Dick, Philip K. (1991). A Scanner Darkly. Vintage. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-679-73665-3.

- May, Julian (11 April 1994). Jack the Bodiless. Random House Value Publishing. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-517-11644-9.

- Dillard, Annie (8 February 2000). For the Time Being. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-70347-8.

- Clarke, Arthur c. (2001). The Light of Other Days. Tom Doherty Associates, LLC. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-8125-7640-5.

- DeLillo, Don (2010). Point Omega. Scribner.

- "The Divine Milieu by Frederick Hart". www.jeanstephengalleries.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- "UDQuickly Past Scribblings". campus.udayton.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2009.[permanent dead link]

- "National Gallery of Victoria Educational Resource" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2009.

- "When life finds its way". www.westcorkpeople.ie. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Ventureyra, Scott (20 January 2015). "Challenging the Rehabilitation of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin". Crisis Magazine. Sophia Institute Press. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Krauss, Lawrence (12 May 2007), "More Dangerous Than Nonsense" (PDF), New Scientist, 194 (2603): 53, doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(07)61199-3, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2011.

- "white gardenia - interview w/ frank tipler (discussion on richard dawkins stephen hawking more." Retrieved 26 September 2022 – via www.youtube.com.

- "Q&A with Frank Tipler". Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Segundo, Juan Luis (1972). Evolution and Guilt. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-88344-480-1.

- 1976. Symbolic Exchange and Death. Jean Baudrillard. "Shadow, spectre, reflection, image; a material spirit almost remains visible, the primitive double generally passes for the crude prefiguration of the soul and consciousness in accordance with an increasing sublimation and a spiritual 'hominisation', as in Teilhard de Chardin: towards the apogee of a single God and a universal morality. But this single God has everything to do with the form of a unified political power, and nothing to do with the primitive gods. In the same way, soul and consciousness have everything to do with a principle of the subject's unification, and nothing to do with the primitive double. On the contrary, the historical advent of the 'soul' puts an end to a proliferating exchange with spirits and doubles which, as an indirect consequence, gives rise to another figure of the double, wending its diabolical way just beneath the surface of Western reason. Once again, this figure has everything to do with the Western figure of alienation, and nothing to do with the primitive double. The telescoping of the two under the sign of psychology (conscious or unconscious) is only a misleading rewriting."

- "Reversibility: Baudrillard's "One Great Thought"". Archived from the original on 30 June 2022.

- Teillard-Chambon, Marguerite, ed. (1956). Lettres de voyage 1923-1939, de Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (in French). Paris: Bernard Grasset.

- Teillard-Chambon, Marguerite, ed. (1957). Nouvelles lettres de voyage 1939-1955, de Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (in French). Paris: Bernard Grasset.

- Teillard-Chambon, Marguerite, ed. (1961). Genèse d'une pensée, Lettres 1914-1919, de Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (in French). Paris: Bernard Grasset.

- Ankerberg, John; John Weldon (1996). Encyclopedia of New Age Beliefs. Harvest House Publishers. pp. 661–. ISBN 978-1-56507-160-5.

- "Royal Wedding: Read the Stirring Sermon by Most Rev. Michael Curry". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. 19 May 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

Further reading

- Amir Aczel, The Jesuit and the Skull: Teilhard de Chardin, Evolution and the Search for Peking Man (Riverhead Hardcover, 2007)

- Pope Benedict XVI, The Spirit of the Liturgy (Ignatian Press 2000)

- Pope Benedict XVI, Introduction to Christianity (Ignatius Press, Revised edition, 2004)

- John Cowburn, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a Selective Summary of His Life (Mosaic Press 2013)

- Claude Cuenot, Science and Faith in Teilhard de Chardin (Garstone Press, 1967)

- Andre Dupleix, 15 Days of Prayer with Teilhard de Chardin (New City Press, 2008)

- Enablers, T.C., 2015. 'Hominising – Realising Human Potential'

- Robert Faricy, Teilhard de Chardin's Theology of Christian in the World (Sheed and Ward 1968)

- Robert Faricy, The Spirituality of Teilhard de Chardin (Collins 1981, Harper & Row 1981)

- Robert Faricy and Lucy Rooney, Praying with Teilhard de Chardin(Queenship 1996)

- David Grumett, Teilhard de Chardin: Theology, Humanity and Cosmos (Peeters 2005)

- Dietrich von Hildebrand, Teilhard de Chardin: A False Prophet (Franciscan Herald Press 1970)

- Dietrich von Hildebrand, Trojan Horse in the City of God

- Dietrich von Hildebrand, Devastated Vineyard

- Thomas M. King, Teilhard's Mass; Approaches to "The Mass on the World" (Paulist Press, 2005)

- Ursula King, Spirit of Fire: The Life and Vision of Teilhard de Chardin maryknollsocietymall.org (Orbis Books, 1996)

- Richard W. Kropf, Teilhard, Scripture and Revelation: A Study of Teilhard de Chardin's Reinterpretation of Pauline Themes (Associated University Press, 1980)

- David H. Lane, The Phenomenon of Teilhard: Prophet for a New Age (Mercer University Press)

- Lubac, Henri de, The Religion of Teilhard de Chardin (Image Books, 1968)

- Lubac, Henri de, The Faith of Teilhard de Chardin (Burnes and Oates, 1965)

- Lubac, Henri de, The Eternal Feminine: A Study of the Text of Teilhard de Chardin (Collins, 1971)

- Lubac, Henri de, Teilhard Explained (Paulist Press, 1968)

- Mary and Ellen Lukas, Teilhard (Doubleday, 1977)

- Jean Maalouf Teilhard de Chardin, Reconciliation in Christ (New City Press, 2002)

- George A. Maloney, The Cosmic Christ: From Paul to Teilhard (Sheed and Ward, 1968)

- Mooney, Christopher, Teilhard de Chardin and the Mystery of Christ (Image Books, 1968)

- Murray, Michael H. The Thought of Teilhard de Chardin (Seabury Press, N.Y., 1966)

- Robert J. O'Connell, Teilhard's Vision of the Past: The Making of a Method, (Fordham University Press, 1982)

- Noel Keith Roberts, From Piltdown Man to Point Omega: the evolutionary theory of Teilhard de Chardin (New York, Peter Lang, 2000)

- James F. Salmon, 'Pierre Teilhard de Chardin' in The Blackwell Companion to Science and Christianity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012)

- Louis M. Savory, Teilhard de Chardin – The Divine Milieu Explained: A Spirituality for the 21st Century (Paulist Press, 2007)

- Robert Speaight, The Life of Teilhard de Chardin (Harper and Row, 1967)

- K.D. Sethna, Teilhard de Chardin and Sri Aurobindo - a focus on fundamentals, Bharatiya Vidya Prakasan, Varanasi (1973)

- K. D. Sethna, The Spirituality of the Future: A search apropos of R. C. Zaehner's study in Sri Aurobindo and Teilhard De Chardin. Fairleigh Dickinson University 1981.

- Helmut de Terra, Memories of Teilhard de Chardin (Harper and Row and Wm Collins Sons & Co., 1964)

- Paul Churchland, "Man and Cosmos"

External links

Pro

- Works by or about Pierre Teilhard de Chardin at Internet Archive

- Teilhard de Chardin (A site devoted to the ideas of Teilhard de Chardin)

- The Teilhard de Chardin Foundation

- The American Teilhard Association

- Teilhard de Chardin A personal website

Contra

- Warning Regarding the Writings of Father Teilhard de Chardin The Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, 1962

- Medawar, Peter (1961). "A review of The Phenomenon of Man". Mind. 70: 99–106. doi:10.1093/mind/LXX.277.99.

- McCarthy, John F. ♦ A review of Teilhardism and the New Religion by Wolfgang Smith 1989

Other

- Works by or about Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Web pages and timeline about the Piltdown forgery hosted by the British Geological Survey

- "Teilhard de Chardin: His Importance in the 21st Century" - Georgetown University - June 23, 2015

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии