astro.wikisort.org - Star

Sagittarius A* (/ˈeɪ stɑːr/ AY star), abbreviated Sgr A* (/ˈsædʒ ˈeɪ stɑːr/ SAJ AY star[3]) is the supermassive black hole[4][5][6] at the Galactic Center of the Milky Way. It is located near the border of the constellations Sagittarius and Scorpius, about 5.6° south of the ecliptic,[7] visually close to the Butterfly Cluster (M6) and Lambda Scorpii.

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Sagittarius |

| Right ascension | 17h 45m 40.0409s |

| Declination | −29° 0′ 28.118″[1] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 8.26×1036 kg (4.154±0.014)×106[2] M☉ |

| Astrometry | |

| Distance | 26,673±42[2] ly (8,178±13[2] pc) |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

The object is a bright and very compact astronomical radio source. The name Sagittarius A* follows from historical reasons. In 1954,[8] John D. Kraus, Hsien-Ching Ko, and Sean Matt listed the radio sources they identified with the Ohio State University radio telescope at 250 MHz. The sources were arranged by constellation and the letter assigned to them was arbitrary, with A denoting the brightest radio source within the constellation. The asterisk * is because its discovery was considered "exciting",[9] in parallel with the nomenclature for excited state atoms which are denoted with an asterisk (e.g. the excited state of Helium would be He*). The asterisk was assigned in 1982 by Robert L. Brown,[10] who understood that the strongest radio emission from the center of the galaxy appeared to be due to a compact nonthermal radio object.

The observations of several stars orbiting Sagittarius A*, particularly star S2, have been used to determine the mass and upper limits on the radius of the object. Based on mass and increasingly precise radius limits, astronomers have concluded that Sagittarius A* must be the Milky Way's central supermassive black hole.[11] The current value of its mass is 4.154±0.014 million solar masses.[2]

Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery that Sagittarius A* is a supermassive compact object, for which a black hole was the only plausible explanation at the time.[12]

On May 12, 2022, astronomers, using the Event Horizon Telescope, released the first image of the accretion disk around the horizon of Sagittarius A* produced using a world-wide network of radio observatories made in April 2017,[13] confirming the object to be a black hole. This is the second confirmed image of a black hole, after Messier 87's supermassive black hole in 2019.[14][15]

Observation and description

![Detection of an unusually bright X-ray flare from Sgr A*[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/85/X-RayFlare-BlackHole-MilkyWay-20140105.jpg/220px-X-RayFlare-BlackHole-MilkyWay-20140105.jpg)

On May 12, 2022, the first image of Sagittarius A* was released by the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. The image, which is based on radio interferometer data taken in 2017, confirms that the object contains a black hole. This is the second image of a black hole.[14][17] This image took five years of calculations to process.[18] The data were collected by eight radio observatories at six geographical sites. Radio images are produced from data by aperture synthesis, usually from night long observations of stable sources. The radio emission from Sgr A* varies on the order of minutes, complicating the analysis.[19]

Their result gives an overall angular size for the source of 51.8±2.3 μas.[17] At a distance of 26,000 light-years (8,000 parsecs), this yields a diameter of 51.8 million kilometres (32.2 million miles). For comparison, Earth is 150 million kilometres (1.0 astronomical unit; 93 million miles) from the Sun, and Mercury is 46 million km (0.31 AU; 29 million mi) from the Sun at perihelion. The proper motion of Sgr A* is approximately −2.70 mas per year for the right ascension and −5.6 mas per year for the declination.[20][21][22] The telescope's measurement of these black holes tested Einstein's theory of relativity more rigorously than has previously been done, and the results match perfectly.[15]

In 2019, measurements made with the High-resolution Airborne Wideband Camera-Plus (HAWC+) mounted in the SOFIA aircraft[23] revealed that magnetic fields cause the surrounding ring of gas and dust, temperatures of which range from −280 to 17,500 °F (99.8 to 9,977.6 K; −173.3 to 9,704.4 °C),[24] to flow into an orbit around Sagittarius A*, keeping black hole emissions low.[25]

Astronomers have been unable to observe Sgr A* in the optical spectrum because of the effect of 25 magnitudes of extinction by dust and gas between the source and Earth.[26]

History

Karl Jansky, considered a father of radio astronomy, discovered in April 1933 that a radio signal was coming from a location in the direction of the constellation of Sagittarius, towards the center of the Milky Way.[27] The radio source later became known as Sagittarius A. His observations did not extend quite as far south as we now know to be the Galactic Center.[28] Observations by Jack Piddington and Harry Minnett using the CSIRO radio telescope at Potts Hill Reservoir, in Sydney discovered a discrete and bright "Sagittarius-Scorpius" radio source,[29] which after further observation with the 80-foot (24-metre) CSIRO radio telescope at Dover Heights was identified in a letter to Nature as the probable Galactic Center.[30]

![ALMA observations of molecular-hydrogen-rich gas clouds, with the area around Sagittarius A* circled[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Cloudlets_swarm_around_our_local_supermassive_black_hole.tif/lossy-page1-220px-Cloudlets_swarm_around_our_local_supermassive_black_hole.tif.jpg)

Later observations showed that Sagittarius A actually consists of several overlapping sub-components; a bright and very compact component, Sgr A*, was discovered on February 13 and 15, 1974, by astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert Brown using the baseline interferometer of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.[32][33] The name Sgr A* was coined by Brown in a 1982 paper because the radio source was "exciting", and excited states of atoms are denoted with asterisks.[34][35]

Since the 1980s, it has been evident that the central component of Sgr A* is likely a black hole. In 1994, infrared and submillimetre spectroscopy studies by a Berkeley team involving Nobel Laureate Charles H. Townes and future Nobel Prize Winner Reinhard Genzel showed that the mass of Sgr A* was tightly concentrated and of the order 3 million Suns.[36]

On October 16, 2002, an international team led by Reinhard Genzel at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics reported the observation of the motion of the star S2 near Sagittarius A* throughout a period of ten years. According to the team's analysis, the data ruled out the possibility that Sgr A* contains a cluster of dark stellar objects or a mass of degenerate fermions, strengthening the evidence for a massive black hole. The observations of S2 used near-infrared (NIR) interferometry (in the Ks-band, i.e. 2.1 μm) because of reduced interstellar extinction in this band. SiO masers were used to align NIR images with radio observations, as they can be observed in both NIR and radio bands. The rapid motion of S2 (and other nearby stars) easily stood out against slower-moving stars along the line-of-sight so these could be subtracted from the images.[37][38]

![Dusty cloud G2 passes the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Dusty_cloud_G2_passes_the_supermassive_black_hole_at_the_centre_of_the_Milky_Way.jpg/260px-Dusty_cloud_G2_passes_the_supermassive_black_hole_at_the_centre_of_the_Milky_Way.jpg)

The VLBI radio observations of Sagittarius A* could also be aligned centrally with the NIR images, so the focus of S2's elliptical orbit was found to coincide with the position of Sagittarius A*. From examining the Keplerian orbit of S2, they determined the mass of Sagittarius A* to be 4.1±0.6 million solar masses, confined in a volume with a radius no more than 17 light-hours (120 AU [18 billion km; 11 billion mi]).[40] Later observations of the star S14 showed the mass of the object to be about 4.1 million solar masses within a volume with radius no larger than 6.25 light-hours (45 AU [6.7 billion km; 4.2 billion mi]).[41] S175 passed within a similar distance.[42] For comparison, the Schwarzschild radius is 0.08 AU (12 million km; 7.4 million mi). They also determined the distance from Earth to the Galactic Center (the rotational center of the Milky Way), which is important in calibrating astronomical distance scales, as 8,000 ± 600 parsecs (30,000 ± 2,000 light-years). In November 2004, a team of astronomers reported the discovery of a potential intermediate-mass black hole, referred to as GCIRS 13E, orbiting 3 light-years from Sagittarius A*. This black hole of 1,300 solar masses is within a cluster of seven stars. This observation may add support to the idea that supermassive black holes grow by absorbing nearby smaller black holes and stars.[citation needed]

After monitoring stellar orbits around Sagittarius A* for 16 years, Gillessen et al. estimated the object's mass at 4.31±0.38 million solar masses. The result was announced in 2008 and published in The Astrophysical Journal in 2009.[43] Reinhard Genzel, team leader of the research, said the study has delivered "what is now considered to be the best empirical evidence that supermassive black holes do really exist. The stellar orbits in the Galactic Center show that the central mass concentration of four million solar masses must be a black hole, beyond any reasonable doubt."[44]

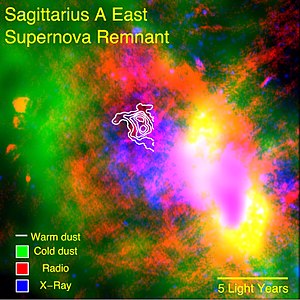

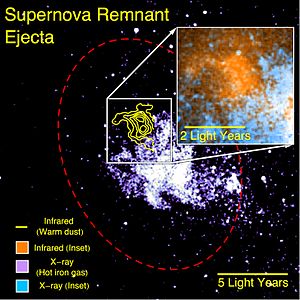

On January 5, 2015, NASA reported observing an X-ray flare 400 times brighter than usual, a record-breaker, from Sgr A*. The unusual event may have been caused by the breaking apart of an asteroid falling into the black hole or by the entanglement of magnetic field lines within gas flowing into Sgr A*, according to astronomers.[16]

On 13 May 2019, astronomers using the Keck Observatory witnessed a sudden brightening of Sgr A*, which became 75 times brighter than usual, suggesting that the supermassive black hole may have encountered another object.[45]

Central black hole

In a paper published on October 31, 2018, the discovery of conclusive evidence that Sagittarius A* is a black hole was announced. Using the GRAVITY interferometer and the four telescopes of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) to create a virtual telescope 130 metres (430 feet) in diameter, astronomers detected clumps of gas moving at about 30% of the speed of light. Emission from highly energetic electrons very close to the black hole was visible as three prominent bright flares. These exactly match theoretical predictions for hot spots orbiting close to a black hole of four million solar masses. The flares are thought to originate from magnetic interactions in the very hot gas orbiting very close to Sagittarius A*.[46][47]

In July 2018, it was reported that S2 orbiting Sgr A* had been recorded at 7,650 km/s (17.1 million mph), or 2.55% the speed of light, leading up to the pericenter approach, in May 2018, at about 120 AU (18 billion km; 11 billion mi) (approximately 1,400 Schwarzschild radii) from Sgr A*. At that close distance to the black hole, Einstein's theory of general relativity (GR) predicts that S2 would show a discernible gravitational redshift in addition to the usual velocity redshift; the gravitational redshift was detected, in agreement with the GR prediction within the 10 percent measurement precision.[48][49]

Assuming that general relativity is still a valid description of gravity near the event horizon, the Sagittarius A* radio emissions are not centered on the black hole, but arise from a bright spot in the region around the black hole, close to the event horizon, possibly in the accretion disc, or a relativistic jet of material ejected from the disc.[50] If the apparent position of Sagittarius A* were exactly centered on the black hole, it would be possible to see it magnified beyond its size, because of gravitational lensing of the black hole. According to general relativity, this would result in a ring-like structure, which has a diameter about 5.2 times the black hole's Schwarzschild radius (10 μas). For a black hole of around 4 million solar masses, this corresponds to a size of approximately 52 μas, which is consistent with the observed overall size of about 50 μas,[50] the size (apparent diameter) of the black hole Sgr A* itself being 20 μas.

Recent lower resolution observations revealed that the radio source of Sagittarius A* is symmetrical.[51] Simulations of alternative theories of gravity depict results that may be difficult to distinguish from GR.[52] However, a 2018 paper predicts an image of Sagittarius A* that is in agreement with recent observations; in particular, it explains the small angular size and the symmetrical morphology of the source.[53]

The mass of Sagittarius A* has been estimated in two different ways:

- Two groups—in Germany and the U.S.—monitored the orbits of individual stars very near to the black hole and used Kepler's laws to infer the enclosed mass. The German group found a mass of 4.31±0.38 million solar masses,[43] whereas the American group found 4.1±0.6 million solar masses.[41] Given that this mass is confined inside a 44-million-kilometre-diameter sphere, this yields a density ten times higher than previous estimates.[citation needed]

- More recently, measurement of the proper motions of a sample of several thousand stars within approximately one parsec from the black hole, combined with a statistical technique, has yielded both an estimate of the black hole's mass at 3.6+0.2

−0.4×106 M☉, plus a distributed mass in the central parsec amounting to (1±0.5)×106 M☉.[54] The latter is thought to be composed of stars and stellar remnants.[citation needed]

The comparatively small mass of this supermassive black hole, along with the low luminosity of the radio and infrared emission lines, imply that the Milky Way is not a Seyfert galaxy.[26]

Ultimately, what is seen is not the black hole itself, but observations that are consistent only if there is a black hole present near Sgr A*. In the case of such a black hole, the observed radio and infrared energy emanates from gas and dust heated to millions of degrees while falling into the black hole.[46] The black hole itself is thought to emit only Hawking radiation at a negligible temperature, on the order of 10−14 kelvin.[citation needed]

The European Space Agency's gamma-ray observatory INTEGRAL observed gamma rays interacting with the nearby giant molecular cloud Sagittarius B2, causing X-ray emission from the cloud. The total luminosity from this outburst (L≈1,5×1039 erg/s) is estimated to be a million times stronger than the current output from Sgr A* and is comparable with a typical active galactic nucleus.[55][56] In 2011 this conclusion was supported by Japanese astronomers observing the Milky Way's center with the Suzaku satellite.[57]

In July 2019, astronomers reported finding a star, S5-HVS1, traveling 1,755 km/s (3.93 million mph) or 0.006 c. The star is in the Grus (or Crane) constellation in the southern sky, and about 29,000 light-years from Earth, and may have been propelled out of the Milky Way galaxy after interacting with Sagittarius A*.[58][59]

Orbiting stars

![Inferred orbits of 6 stars around supermassive black hole candidate Sagittarius A* at the Milky Way's center[60]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Galactic_centre_orbits.svg/220px-Galactic_centre_orbits.svg.png)

![Stars moving around Sagittarius A* as seen in 2018[61][62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/SgrA2018.gif/220px-SgrA2018.gif)

![Stars moving around Sagittarius A* as seen in 2021[63][64][65]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/SgrA2021.gif/220px-SgrA2021.gif)

There are a number of stars in close orbit around Sagittarius A*, which are collectively known as "S stars".[66] These stars are observed primarily in K band infrared wavelengths, as interstellar dust drastically limits visibility in visible wavelengths. This is a rapidly changing field—in 2011, the orbits of the most prominent stars then known were plotted in the diagram at left, showing a comparison between their orbits and various orbits in the solar system.[62] Since then, S62 has been found to approach even more closely than those stars.[67]

The high velocities and close approaches to the supermassive black hole makes these stars useful to establish limits on the physical dimensions of Sagittarius A*, as well as to observe general-relativity associated effects like periapse shift of their orbits. An active watch is maintained for the possibility of stars approaching the event horizon close enough to be disrupted, but none of these stars are expected to suffer that fate. The observed distribution of the planes of the orbits of the S stars limits the spin of Sagittarius A* to less than 10% of its theoretical maximum value.[68]

As of 2020[update], S4714 is the current record holder of closest approach to Sagittarius A*, at about 12.6 AU (1.88 billion km), almost as close as Saturn gets to the Sun, traveling at about 8% of the speed of light. These figures given are approximate, the formal uncertainties being 12.6±9.3 AU and 23,928±8,840 km/s. Its orbital period is 12 years, but an extreme eccentricity of 0.985 gives it the close approach and high velocity.[69]

An excerpt from a table of this cluster (see Sagittarius A* cluster), featuring the most prominent members. In the below table, id1 is the star's name in the Gillessen catalog and id2 in the catalog of the University of California, Los Angeles. a, e, i, Ω and ω are standard orbital elements, with a measured in arcseconds. Tp is the epoch of pericenter passage, P is the orbital period in years and Kmag is the infrared K-band apparent magnitude of the star. q and v are the pericenter distance in AU and pericenter speed in percent of the speed of light.[70]

| id1 | id2 | a | e | i (°) | Ω (°) | ω (°) | Tp (yr) | P (yr) | Kmag | q (AU) | v (%c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S0-1 | 0.5950 | 0.5560 | 119.14 | 342.04 | 122.30 | 2001.800 | 166.0 | 14.70 | 2160.7 | 0.55 |

| S2 | S0-2 | 0.1251 | 0.8843 | 133.91 | 228.07 | 66.25 | 2018.379 | 16.1 | 13.95 | 118.4 | 2.56 |

| S8 | S0-4 | 0.4047 | 0.8031 | 74.37 | 315.43 | 346.70 | 1983.640 | 92.9 | 14.50 | 651.7 | 1.07 |

| S12 | S0-19 | 0.2987 | 0.8883 | 33.56 | 230.10 | 317.90 | 1995.590 | 58.9 | 15.50 | 272.9 | 1.69 |

| S13 | S0-20 | 0.2641 | 0.4250 | 24.70 | 74.50 | 245.20 | 2004.860 | 49.0 | 15.80 | 1242.0 | 0.69 |

| S14 | S0-16 | 0.2863 | 0.9761 | 100.59 | 226.38 | 334.59 | 2000.120 | 55.3 | 15.70 | 56.0 | 3.83 |

| S62 | 0.0905 | 0.9760 | 72.76 | 122.61 | 42.62 | 2003.330 | 9.9 | 16.10 | 16.4 | 7.03 | |

| S4714 | 0.102 | 0.985 | 127.7 | 129.28 | 357.25 | 2017.29 | 12.0 | 17.7 | 12.6 | 8.0 |

Discovery of G2 gas cloud on an accretion course

First noticed as something unusual in images of the center of the Milky Way in 2002,[71] the gas cloud G2, which has a mass about three times that of Earth, was confirmed to be likely on a course taking it into the accretion zone of Sgr A* in a paper published in Nature in 2012.[72] Predictions of its orbit suggested it would make its closest approach to the black hole (a perinigricon) in early 2014, when the cloud was at a distance of just over 3,000 times the radius of the event horizon (or ≈260 AU, 36 light-hours) from the black hole. G2 has been observed to be disrupting since 2009,[72] and was predicted by some to be completely destroyed by the encounter, which could have led to a significant brightening of X-ray and other emission from the black hole. Other astronomers suggested the gas cloud could be hiding a dim star, or a binary star merger product, which would hold it together against the tidal forces of Sgr A*, allowing the ensemble to pass by without any effect.[73] In addition to the tidal effects on the cloud itself, it was proposed in May 2013[74] that, prior to its perinigricon, G2 might experience multiple close encounters with members of the black-hole and neutron-star populations thought to orbit near the Galactic Center, offering some insight to the region surrounding the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.[75]

The average rate of accretion onto Sgr A* is unusually small for a black hole of its mass[76] and is only detectable because it is so close to Earth. It was thought that the passage of G2 in 2013 might offer astronomers the chance to learn much more about how material accretes onto supermassive black holes. Several astronomical facilities observed this closest approach, with observations confirmed with Chandra, XMM, VLA, INTEGRAL, Swift, Fermi and requested at VLT and Keck.[77]

Simulations of the passage were made before it happened by groups at ESO[78] and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL).[79]

As the cloud approached the black hole, Dr. Daryl Haggard said, "It's exciting to have something that feels more like an experiment", and hoped that the interaction would produce effects that would provide new information and insights.[80]

Nothing was observed during and after the closest approach of the cloud to the black hole, which was described as a lack of "fireworks" and a "flop".[81] Astronomers from the UCLA Galactic Center Group published observations obtained on March 19 and 20, 2014, concluding that G2 was still intact (in contrast to predictions for a simple gas cloud hypothesis) and that the cloud was likely to have a central star.[82]

An analysis published on July 21, 2014, based on observations by the ESO's Very Large Telescope in Chile, concluded alternatively that the cloud, rather than being isolated, might be a dense clump within a continuous but thinner stream of matter, and would act as a constant breeze on the disk of matter orbiting the black hole, rather than sudden gusts that would have caused high brightness as they hit, as originally expected. Supporting this hypothesis, G1, a cloud that passed near the black hole 13 years ago, had an orbit almost identical to G2, consistent with both clouds, and a gas tail thought to be trailing G2, all being denser clumps within a large single gas stream.[81][83]

Professor Andrea Ghez et al. suggested in 2014 that G2 is not a gas cloud but rather a pair of binary stars that had been orbiting the black hole in tandem and merged into an extremely large star.[73][84]

See also

- Galactic Center GeV excess – Unexplained gamma-ray radiation in the center of the Milky Way galaxy

- List of nearest known black holes

Notes

- Reid and Brunthaler 2004

- The GRAVITY collaboration (April 2019). "A geometric distance measurement to the Galactic center black hole with 0.3% uncertainty". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 625: L10. arXiv:1904.05721. Bibcode:2019A&A...625L..10G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935656. S2CID 119190574. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- "Astronomers reveal first image of the black hole at the heart of our galaxy". Event Horizon Telescope. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- Parsons, Jeff (October 31, 2018). "Scientists find proof a supermassive black hole is lurking at the centre of the Milky Way". Metro. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Mosher, Dave; Business Insider (October 31, 2018). "A 'mind-boggling' telescope observation has revealed the point of no return for our galaxy's monster black hole". The Middletown Press. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Plait, Phil (November 7, 2018). "Astronomers See Material Orbiting a Black Hole *Right* at the Edge of Forever". Bad Astronomy. Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- Calculated using Equatorial and Ecliptic Coordinates Archived July 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine calculator

- Kraus, J. D.; Ko, H. C.; Matt, S. (December 1954). "Galactic and localized source observations at 250 megacycles per second". The Astronomical Journal. 59: 439–443. Bibcode:1954AJ.....59..439K. doi:10.1086/107059. ISSN 0004-6256 – via The ADS.

- Goss, W. M.; Brown, Robert L.; Lo, K. Y. (August 8, 2003). "The Discovery of Sgr A*". Astronomische Nachrichten. 324 (S1): 497–504. arXiv:astro-ph/0305074. Bibcode:2003ANS...324..497G. doi:10.1002/asna.200385047. ISSN 0004-6337.

- Brown, Robert L. (November 1, 1982). "Precessing Jets in Sagittarius A: Gas Dynamics in the Central Parsec of the Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal. 262: 110–119. Bibcode:1982ApJ...262..110B. doi:10.1086/160401. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- Henderson, Mark (December 9, 2009). "Astronomers confirm black hole at the heart of the Milky Way". Times Online. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2020". October 6, 2020. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- Bower, Geoffrey C. (May 2022). "Focus on First Sgr A* Results from the Event Horizon Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- "Astronomers reveal first image of the black hole at the heart of our galaxy". eso.org. May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- Overbye, Dennis (May 12, 2022). "The Milky Way's Black Hole Comes to Light". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- Chou, Felicia; Anderson, Janet; Watzke, Megan (January 5, 2015). "NASA's Chandra Detects Record-Breaking Outburst from Milky Way's Black Hole". NASA. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (May 1, 2022). "First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 930 (2): L12. Bibcode:2022ApJ...930L..12E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6674. eISSN 2041-8213. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 248744791.

- Hensley, Kerry (May 12, 2022). "First Image of the Milky Way's Supermassive Black Hole". AAS Nova. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (May 1, 2022). "First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. III. Imaging of the Galactic Center Supermassive Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 930 (2): L14. Bibcode:2022ApJ...930L..14E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6429. eISSN 2041-8213. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 248744704.

- Backer and Sramek 1999, § 3

- "Focus on the First Event Horizon Telescope Results – The Astrophysical Journal Letters – IOPscience". iopscience.iop.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- Overbye, Dennis (April 10, 2019). "Black Hole Picture Revealed for the First Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- "HAWC+, the Far-Infrared Camera and Polarimeter for SOFIA". 2018. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- "The Milky Way's Monster Black Hole Has a Cool Gas Halo – Literally". Space.com. June 5, 2019. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- "Magnetic Fields May Muzzle Milky Way's Monster Black Hole". Space.com. June 14, 2019. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- Osterbrock and Ferland 2006, p. 390

- "Karl Jansky: The Father of Radio Astronomy". August 29, 2012. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Goss, W. M.; McGee, R. X. (1996). "The Discovery of the Radio Source Sagittarius A (Sgr A)". The Galactic Center, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. 102: 369. Bibcode:1996ASPC..102..369G. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Piddington, J. H.; Minnett, H. C. (December 1, 1951). "Observations of Galactic Radiation at Frequencies of 1200 and 3000 Mc/s". Australian Journal of Scientific Research a Physical Sciences. 4 (4): 459. Bibcode:1951AuSRA...4..459P. doi:10.1071/CH9510459. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- McGee, R. X.; Bolton, J. G. (May 1, 1954). "Probable observation of the galactic nucleus at 400 Mc./s". Nature. 173 (4412): 985–987. Bibcode:1954Natur.173..985M. doi:10.1038/173985b0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4188235. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- "Cloudlets swarm around our local supermassive black hole". www.eso.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Balick, B.; Brown, R. L. (December 1, 1974). "Intense sub-arcsecond structure in the galactic center". Astrophysical Journal. 194 (1): 265–270. Bibcode:1974ApJ...194..265B. doi:10.1086/153242. S2CID 121802758.

- Melia 2007, p. 7

- Goss, W. M.; Brown, Robert L.; Lo, K. Y. (May 6, 2003). "The Discovery of Sgr A*". Astronomische Nachrichten. 324 (1): 497. arXiv:astro-ph/0305074. Bibcode:2003ANS...324..497G. doi:10.1002/asna.200385047.

- Brown, R. L. (November 1, 1982). "Precessing jets in Sagittarius A – Gas dynamics in the central parsec of the galaxy". Astrophysical Journal, Part 1. 262: 110–119. Bibcode:1982ApJ...262..110B. doi:10.1086/160401.

- Genzel, R; Hollenbach, D; Townes, C H (1994). "The nucleus of our Galaxy". Reports on Progress in Physics. 57 (5): 417–479. Bibcode:1994RPPh...57..417G. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/57/5/001. ISSN 0034-4885. S2CID 250900662.

- Schödel et al. 2002

- Sakai, Shoko; Lu, Jessica R.; Ghez, Andrea; Jia, Siyao; Do, Tuan; Witzel, Gunther; Gautam, Abhimat K.; Hees, Aurelien; Becklin, E.; Matthews, K.; Hosek, M. W. (March 5, 2019). "The Galactic Center: An Improved Astrometric Reference Frame for Stellar Orbits around the Supermassive Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal. 873 (1): 65. arXiv:1901.08685. Bibcode:2019ApJ...873...65S. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab0361. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 119331998.

- "Best View Yet of Dusty Cloud Passing Galactic Centre Black Hole". Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Ghez et al. (2003) "The First Measurement of Spectral Lines in a Short-Period Star Bound to the Galaxy's Central Black Hole: A Paradox of Youth" Astrophysical Journal 586 L127

- Ghez, A. M.; et al. (December 2008). "Measuring Distance and Properties of the Milky Way's Central Supermassive Black Hole with Stellar Orbits". Astrophysical Journal. 689 (2): 1044–1062. arXiv:0808.2870. Bibcode:2008ApJ...689.1044G. doi:10.1086/592738. S2CID 18335611.

- Gillessen, S.; Plewa, P. M.; Eisenhauer, F.; Sari, R.; Waisberg, I.; Habibi, M.; Pfuhl, O.; George, E.; Dexter, J. (2017). "An Update on Monitoring Stellar Orbits in the Galactic Center". The Astrophysical Journal. 837 (1): 30. arXiv:1611.09144. Bibcode:2017ApJ...837...30G. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa5c41. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 119087402.

- Gillessen et al. 2009

- O'Neill 2008

- "Our Galaxy's Supermassive Black Hole Has Emitted a Mysteriously Bright Flare". Science Alert. August 12, 2019. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Abuter, R.; Amorim, A.; Bauböck, M.; Berger, J. P.; Bonnet, H.; Brandner, W.; Clénet, Y.; Coudé Du Foresto, V.; De Zeeuw, P. T.; Deen, C.; Dexter, J.; Duvert, G.; Eckart, A.; Eisenhauer, F.; Förster Schreiber, N. M.; Garcia, P.; Gao, F.; Gendron, E.; Genzel, R.; Gillessen, S.; Guajardo, P.; Habibi, M.; Haubois, X.; Henning, T.; Hippler, S.; Horrobin, M.; Huber, A.; Jiménez Rosales, A.; Jocou, L.; et al. (2018). "Detection of orbital motions near the last stable circular orbit of the massive black hole SgrA". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 618: L10. arXiv:1810.12641. Bibcode:2018A&A...618L..10G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834294. S2CID 53613305.

- "Most Detailed Observations of Material Orbiting close to a Black Hole". European Southern Observatory (ESO). Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Genzel; et al. (July 26, 2018). "Detection of the gravitational redshift in the orbit of the star S2 near the Galactic centre massive black hole". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 615: L15. arXiv:1807.09409. Bibcode:2018A&A...615L..15G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833718. S2CID 118891445. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- "Star spotted speeding near black hole at centre of Milky Way – Chile's Very Large Telescope tracks S2 star as it reaches mind-boggling speeds by supermassive black hole". The Guardian. July 26, 2017. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- Lu, R.; et al. (2018). "Detection of intrinsic source structure at ~3 Schwarzschild radii with Millimeter-VLBI observations of Sgr A*". Astrophysical Journal. 859 (1): 60. arXiv:1805.09223. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aabe2e. S2CID 51917277.

- Issaoun, S. (January 18, 2019). "The Size, Shape, and Scattering of Sagittarius A* at 86 GHz: First VLBI with ALMA". The Astrophysical Journal. 871 (1): 30. arXiv:1901.06226. Bibcode:2019ApJ...871...30I. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaf732. S2CID 84180473.

- Rezzolla, Luciano (April 17, 2018). "Astrophysicists Test Theories of Gravity with Black Hole Shadows". SciTech Daily. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Revealing the black hole at the heart of the galaxy". Netherlands Research School for Astronomy. January 22, 2019. Archived from the original on March 18, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019 – via Phys.org.

- Schödel et al. 2009

- "Integral rolls back history of Milky Way's super-massive black hole". Hubble News Desk. January 28, 2005. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- M. G. Revnivtsev; et al. (2004). "Hard X-ray view of the past activity of Sgr A* in a natural Compton mirror". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 425 (3): L49–L52. arXiv:astro-ph/0408190. Bibcode:2004A&A...425L..49R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200400064. S2CID 18872302.

- M. Nobukawa; et al. (2011). "New Evidence for High Activity of the Supermassive Black Hole in our Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 739 (2): L52. arXiv:1109.1950. Bibcode:2011ApJ...739L..52N. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/739/2/L52. S2CID 119244398.

- Overbye, Dennis (November 14, 2019). "A Black Hole Threw a Star Out of the Milky Way Galaxy – So long, S5-HVS1, we hardly knew you". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Koposov, Sergey E.; et al. (November 11, 2019). "Discovery of a nearby 1700 km/s star ejected from the Milky Way by Sgr A*". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. arXiv:1907.11725. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz3081. S2CID 198968336.

- Eisenhauer, F.; et al. (July 20, 2005). "SINFONI in the Galactic Center: Young Stars and Infrared Flares in the Central Light-Month". The Astrophysical Journal. 628 (1): 246–259. arXiv:astro-ph/0502129. Bibcode:2005ApJ...628..246E. doi:10.1086/430667. S2CID 122485461.

- "First Successful Test of Einstein's General Relativity Near Supermassive Black Hole – Culmination of 26 years of ESO observations of the heart of the Milky Way". www.eso.org. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- GRAVITY Collaboration; Abuter, R.; Amorim, A.; Anugu, N.; Bauböck, M.; Benisty, M.; Berger, J. P.; Blind, N.; Bonnet, H.; Brandner, W.; Buron, A. (July 2018). "Detection of the gravitational redshift in the orbit of the star S2 near the Galactic centre massive black hole". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 615: L15. arXiv:1807.09409. Bibcode:2018A&A...615L..15G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833718. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 118891445. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- "Watch stars move around the Milky Way's supermassive black hole in deepest images yet". www.eso.org. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- GRAVITY Collaboration; Stadler, J.; Drescher, A. (December 14, 2021). "Deep images of the Galactic center with GRAVITY". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 657: A82. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142459. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 245131155. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- GRAVITY Collaboration; Abuter, R.; Aimar, N.; Amorim, A.; Ball, J.; Bauböck, M.; Gillessen, S.; Widmann, F.; Heissel, G. (December 14, 2021). "Mass distribution in the Galactic Center based on interferometric astrometry of multiple stellar orbits". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 657: L12. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142465. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 245131377. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- Eckart, A.; Genzel, R.; Ott, T.; Schödel, R. (April 11, 2002). "Stellar orbits near Sagittarius A*". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 331 (4): 917–934. arXiv:astro-ph/0201031. Bibcode:2002MNRAS.331..917E. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05237.x. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 11167996.

- Peissker, Florian; Eckart, Andreas; Parsa, Marzieh (January 2020). "S62 on a 9.9 year orbit around SgrA*". The Astrophysical Journal. 889 (1): 61. arXiv:2002.02341. Bibcode:2020ApJ...889...61P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab5afd. S2CID 211043784.

- "Milky Way's Supermassive Black Hole is Spinning Slowly, Astronomers Say". October 28, 2020. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Peißker, Florian; Eckart, Andreas; Zajaček, Michal; Basel, Ali; Parsa, Marzieh (August 2020). "S62 and S4711: Indications of a Population of Faint Fast-moving Stars inside the S2 Orbit—S4711 on a 7.6 yr Orbit around Sgr A*". The Astrophysical Journal. 889 (50): 5. arXiv:2008.04764. Bibcode:2020ApJ...899...50P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab9c1c. S2CID 221095771.

- Næss, S. (October 4, 2019). "Galactic center S-star orbital parameters".

- Matson, John (October 22, 2012). "Gas Guzzler: Cloud Could Soon Meet Its Demise in Milky Way's Black Hole". Scientific American. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- Gillessen, S.; Genzel; Fritz; Quataert; Alig; Burkert; Cuadra; Eisenhauer; Pfuhl; Dodds-Eden; Gammie; Ott (January 5, 2012). "A gas cloud on its way towards the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Centre". Nature. 481 (7379): 51–54. arXiv:1112.3264. Bibcode:2012Natur.481...51G. doi:10.1038/nature10652. PMID 22170607. S2CID 4410915.

- Witzel, G.; Ghez, A. M.; Morris, M. R.; Sitarski, B. N.; Boehle, A.; Naoz, S.; Campbell, R.; Becklin, E. E.; G. Canalizo; Chappell, S.; Do, T.; Lu, J. R.; Matthews, K.; Meyer, L.; Stockton, A.; Wizinowich, P.; Yelda, S. (January 1, 2014). "Detection of Galactic Center Source G2 at 3.8 μm during Periapse Passage". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 796 (1): L8. arXiv:1410.1884. Bibcode:2014ApJ...796L...8W. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/796/1/L8. S2CID 36797915.

- Bartos, Imre; Haiman, Zoltán; Kocsis, Bence; Márka, Szabolcs (May 2013). "Gas Cloud G2 Can Illuminate the Black Hole Population Near the Galactic Center". Physical Review Letters. 110 (22): 221102 (5 pages). arXiv:1302.3220. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110v1102B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.221102. PMID 23767710. S2CID 12284209.

- de la Fuente Marcos, R.; de la Fuente Marcos, C. (August 2013). "Colliding with G2 near the Galactic Centre: a geometrical approach". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 435 (1): L19–L23. arXiv:1306.4921. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.435L..19D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt085. S2CID 119287777.

- Morris, Mark (January 4, 2012). "Astrophysics: The Final Plunge". Nature. 481 (7379): 32–33. Bibcode:2012Natur.481...32M. doi:10.1038/nature10767. PMID 22170611. S2CID 664513.

- Gillessen. "Wiki Page of Proposed Observations of G2 Passage". Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- "A Black Hole's Dinner is Fast Approaching". ESO. December 14, 2011. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- Robert H Hirschfeld (October 22, 2012). "Milky Way's black hole getting ready for snack". [www.Llnl.gov Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory]. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- space.com, Doomed Space Cloud Nears Milky Way's Black Hole as Scientists Watch, 28 April 2014 Archived 3 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine "Cosmic encounter that might reveal new secrets on how such supermassive black holes evolve"; "We get to watch it unfolding in a human lifetime, which is very unusual and very exciting"

- Cowen, Ron (2014). "Why galactic black hole fireworks were a flop : Nature News & Comment". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.15591. S2CID 124346286. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- A. M. Ghez; G . Witzel; B. Sitarski; L. Meyer; S. Yelda; A. Boehle; E. E. Becklin; R. Campbell; G. Canalizo; T. Do; J. R. Lu; K. Matthews; M. R. Morris; A. Stockton (May 2, 2014). "Detection of Galactic Center Source G2 at 3.8 micron during Periapse Passage Around the Central Black Hole". The Astronomer's Telegram. 6110 (6110): 1. Bibcode:2014ATel.6110....1G. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- Pfuhl, Oliver; Gillessen, Stefan; Eisenhauer, Frank; Genzel, Reinhard; Plewa, Philipp M.; Thomas Ott; Ballone, Alessandro; Schartmann, Marc; Burkert, Andreas (2015). "The Galactic Center Cloud G2 and its Gas Streamer". The Astrophysical Journal. 798 (2): 111. arXiv:1407.4354. Bibcode:2015ApJ...798..111P. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/798/2/111. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 118440030.

- "How G2 survived the black hole at our Milky Way's heart - EarthSky.org". November 4, 2014. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- "Simulation of gas cloud after close approach to the black hole at the centre of the Milky Way". ESO. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

References

- Backer, D. C. & Sramek, R. A. (October 20, 1999). "Proper Motion of the Compact, Nonthermal Radio Source in the Galactic Center, Sagittarius A*". The Astrophysical Journal. 524 (2): 805–815. arXiv:astro-ph/9906048. Bibcode:1999ApJ...524..805B. doi:10.1086/307857. S2CID 18858138.

- Gillessen, Stefan; et al. (February 23, 2009). "Monitoring stellar orbits around the Massive Black Hole in the Galactic Center". The Astrophysical Journal. 692 (2): 1075–1109. arXiv:0810.4674. Bibcode:2009ApJ...692.1075G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/692/2/1075. S2CID 1431308.

- Melia, Fulvio (2007). The Galactic Supermassive Black Hole. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13129-0.

- O'Neill, Ian (December 10, 2008). "Beyond Any Reasonable Doubt: A Supermassive Black Hole Lives in Centre of Our Galaxy". Universe Today.

- Osterbrock, Donald E. & Ferland, Gary J. (2006). Astrophysics of Gaseous Nebulae and Active Galactic Nuclei (2nd ed.). University Science Books. ISBN 978-1-891389-34-4.

- Reid, M.J.; Brunthaler, A. (2004). "Sgr A* – Radio-source". Astrophysical Journal. 616 (2): 872–884. arXiv:astro-ph/0408107. Bibcode:2004ApJ...616..872R. doi:10.1086/424960. S2CID 16568545.

- Schödel, R.; et al. (October 17, 2002). "A star in a 15.2-year orbit around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way". Nature. 419 (6908): 694–696. arXiv:astro-ph/0210426. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..694S. doi:10.1038/nature01121. PMID 12384690. S2CID 4302128.

- Schödel, R.; Merritt, D.; Eckart, A. (July 2009). "The nuclear star cluster of the Milky Way: Proper motions and mass". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 502 (1): 91–111. arXiv:0902.3892. Bibcode:2009A&A...502...91S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200810922. S2CID 219559.

Further reading

- Melia, Fulvio (2003). The Black Hole at the Center of our Galaxy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691095059.

- Doeleman, Sheperd; et al. (September 4, 2008). "Event-horizon-scale structure in the supermassive black hole candidate at the Galactic Centre". Nature. 455 (7209): 78–80. arXiv:0809.2442. Bibcode:2008Natur.455...78D. doi:10.1038/nature07245. PMID 18769434. S2CID 4424735.

- Eckart, A.; Schödel, R.; Straubmeier, C. (2005). The Black Hole at the Center of the Milky Way. London: Imperial College Press.

- Eisenhauer, F.; et al. (October 23, 2003). "A Geometric Determination of the Distance to the Galactic Center". The Astrophysical Journal. 597 (2): L121–L124. arXiv:astro-ph/0306220. Bibcode:2003ApJ...597L.121E. doi:10.1086/380188. S2CID 16425333.

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (April 10, 2019). "First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 875 (1): L1. arXiv:1906.11238. Bibcode:2019ApJ...875L...1E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab0ec7. S2CID 145906806.

- Ghez, A. M.; et al. (March 12, 2003). "The First Measurement of Spectral Lines in a Short-Period Star Bound to the Galaxy's Central Black Hole: A Paradox of Youth". The Astrophysical Journal. 586 (2): L127–L131. arXiv:astro-ph/0302299. Bibcode:2003ApJ...586L.127G. doi:10.1086/374804. S2CID 11388341.

- Ghez, A. M.; et al. (December 2008). "Measuring Distance and Properties of the Milky Way's Central Supermassive Black Hole with Stellar Orbits". Astrophysical Journal. 689 (2): 1044–1062. arXiv:0808.2870. Bibcode:2008ApJ...689.1044G. doi:10.1086/592738. S2CID 18335611.

- Reynolds, C. (September 4, 2008). "Astrophysics: Bringing black holes into focus". Nature. 455 (7209): 39–40. Bibcode:2008Natur.455...39R. doi:10.1038/455039a. PMID 18769426. S2CID 205040663.

- Wheeler, J. Craig (2007). Cosmic Catastrophes: Exploding Stars, Black Holes, and Mapping the Universe (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85714-7.

External links

- UCLA Galactic Center Group – latest results retrieved 8/12/2009

- Is there a Supermassive Black Hole at the Center of the Milky Way? (arXiv preprint)

- 2004 paper deducing mass of central black hole from orbits of 7 stars (arXiv preprint)

- ESO video clip of orbiting star (533 KB MPEG Video)

- The Proper Motion of Sgr A* and the Mass of Sgr A* (PDF)

- NRAO article regarding VLBI radio imaging of Sgr A*

- Peering into a Black Hole, 2015 New York Times video

- Image of supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (2022), Harvard Center for Astrophysics

- Video (65:30) – EHT conference presenting first image of Sgr A* on YouTube (NSF; 12 May 2022)

На других языках

- [en] Sagittarius A*

[es] Sagitario A*

Sagitario A* —pronunciado Sagitario A estrella[1] y abreviado Sgr A*— es el agujero negro supermasivo del centro galáctico de la Vía Láctea.[ru] Стрелец A*

Стрелец A* (лат. Sagittarius A*, Sgr A*; произносится «Стреле́ц А со звёздочкой») — компактный радиоисточник, находящийся в центре Млечного Пути, входит в состав радиоисточника Стрелец А. Излучает также в инфракрасном, рентгеновском и других диапазонах. Представляет собой высокоплотный объект — сверхмассивную чёрную дыру[6][7][8], окружённую горячим радиоизлучающим газовым облаком диаметром около 1,8 пк[9]. Расстояние до радиоисточника составляет (27,00 ± 0,10) тыс. св. лет, масса центрального объекта равна (4,297 ± 0,042) млн M⊙[3][10]. Данные с радиотелескопа VLBA свидетельствуют, что непосредственно на долю самой чёрной дыры приходится минимум четверть от общей массы объекта Sgr A*, а остальная часть массы приходится на окружающую чёрную дыру материю, а также соседние с ней звёзды и облака газа[11].Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии